some of you who have been listening perhaps a little too obsessively might recall a seemingly trivial anecdote in the opening comments of episode six involving an impish acquaintance of mine who stole from me the recording of the story Oscar called The Knee. This acquaintance, whom I’ll refer to as Ahab Cloud here for reasons I’ll soon get to, used that recording as a road map of sorts for a no budget film I happened, by chance, to catch at a ramshackle film festival on winter night. As incredible as it might seem, Mr. Cloud instructed his fledgling troupe of wet-eyed actors to lip sync their lines to Oscar’s tapes in order to dub the field recordings over their mouthing faces in post-production. I was stunned. And angry.

Well, sometime after he disappeared to make his picture I began receiving postcards from Ahab Cloud. Though he signed none of these post cards I knew from our days of mopping up cheap beer with our faces that it was his handwriting. I was an expert in recognizing Cloud’s hand because when I knew him, if nothing else, Mr. Cloud was a writer. Now in this case, I don’t mean writer in the wordsmith mystic visionary artists sense of the word, though he may have been that too in my opinion, but rather I use writer here as a descriptor of a person performing the physical act, just as you might describe someone sitting as a sitter in a pinch. Back in our college and immediate post college days, Ahab wrote anything and everything with indiscriminate ferocity, and he wrote on any surface that provided enough space in which to cram a scrawling.

This is my career strategy, he told me one day while committing the pledge of allegiance to a cafe window using his girlfriend’s black lipstick. To be a writer, he said, One must write. So, I write. Simple. And I encourage you to do the same. You know, to get in the habit. Wax on, etc.

I declined his advice mostly, choosing instead to torture a computer keyboard in my darkest hours, but I did take pleasure watching Ahab perform the act, particularly when under the influence of hallucinogenic substances. I watched as he wrote assembly instructions for model airplanes on sign-in sheets at doctor’s offices. I looked on giggling as he wrote archaic home remedies inside the covers of Psalm Books. Giggled like a schoolboy as he set down Catholic prayers on the backs of his paltry paychecks before handing them over to confused bank tellers. He wrote complicated shopping lists in the margins of every copy of Finnegan’s Wake he could find in every bookstore new and used in a twenty mile radius of our dorm room. He scrawled passages from Heart of Darkness in black magic marker on the skins of kids who passed out at frat parties. Jane Austen quotes on rental agreements. Swedish meatball recipes on sidewalks in chalk. His parents’ personal contact information on subway walls. And so on.

I interpreted this vaudeville act of mischief as the late bloomer rebellion of a kid who had been hemmed in to his academic work too closely during the angst-ridden high school years when most kids are busy piercing various parts of their faces, driving too fast on suburban side roads, or flirting provocatively with gateway drugs. The unintentional bi-product of the draconian practice of study was that when Ahab finally found his college-sized ration of independence, instead of riding a wave of promiscuity or nursing hangovers in psych 101 lecture halls, he let forth the tidal movements of an overly-developed brain flooded with four or five years’ worth of AP Lit and the privately smuggled ravings of Kerouac and Nietzsche. Mr. Cloud’s performance art act of writing was half ironic, half sincere, and one hundred percent lust for life.

The point is, we did have keyboards and computers during our college days so if Mr. Cloud wasn’t such a writer in the most perfunctory sense of the word, then I would have had no way of knowing incontrovertibly it was he sending me those postcards.

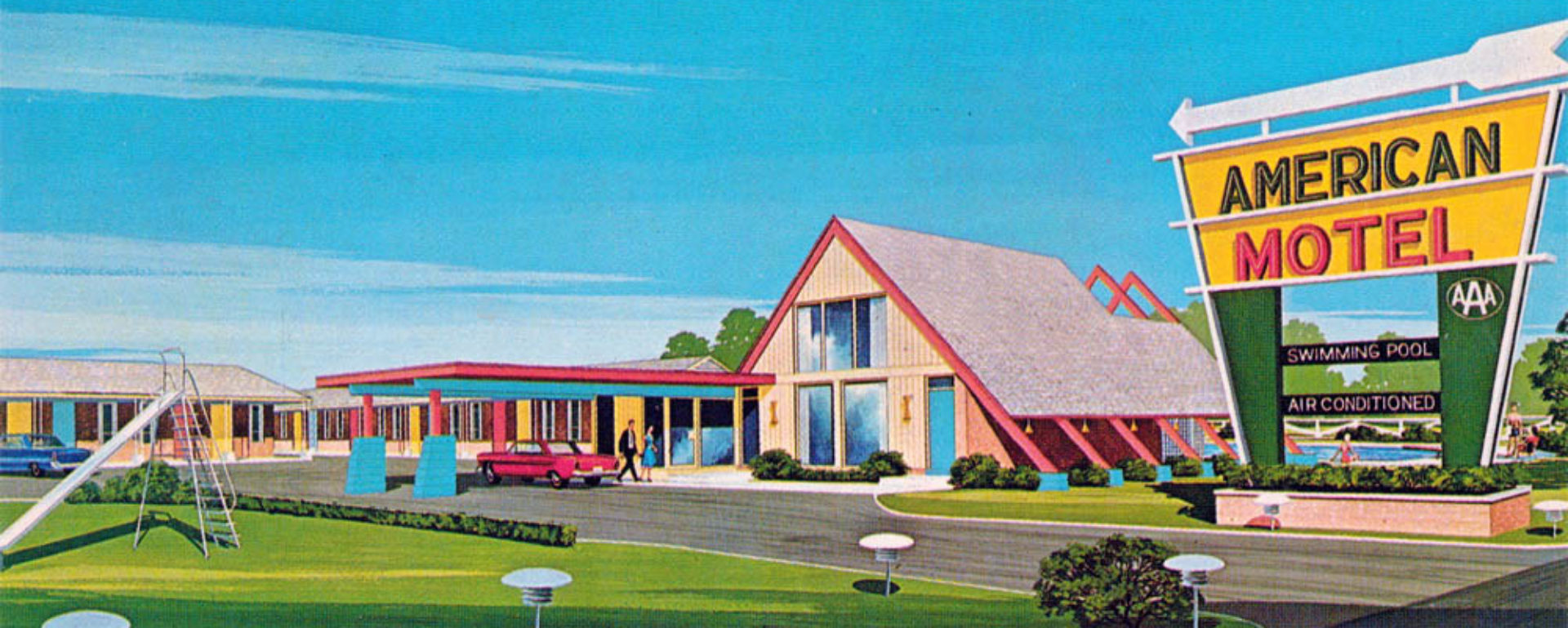

Even knowing Mr. Cloud’s capacity for caprice those postcards baffled me. The fronts all featured pictures of mid-century-ish motels cast in the shimmering colors of Kodachrome daydreams– establishments featuring giant fiberglass statues of gaudily painted cowboys and rocket ships and Indians and baseball players and dinosaurs and flamingos, all of whom loomed ominously over the parking lots outside their respective lobbies, standing tall against landscapes spanning the American geographical spectrum from diamond dessert to gulfstream waters.

On the address sides of the postcards were cryptic messages devoid of salutation as well as signature. From the Atlasta Motel in Boonville Missouri, for instance, Cloud wrote:

This just in: In Texas there was a man so sad he ate his shoe.

A strange message to send a somewhat estranged acquaintance you’ve recently screwed over, I thought. But it got only stranger as more dispatches arrived. The front image of The Mission Auto Court on Rte. 66 in San Bernardino assured me that the rooms contained plenty of “Ice Cold Air Conditioning.” But on the reverse side Mr. Cloud declared:

Fog has been linked to symbolism. From now on, whenever you look at anything through a pale swab of fog remember: you are not seeing the thing itself. What you see is a representation of an abstract principle.A week later I received a seemingly related message written on the back of a card sent from The Fantasy Motel in East Limon Colorado, which, incidentally for those traveling through area, boasts a heated pool and free HBO. Verbatim, Mr. Cloud’s words ran:

Specialists predict that the usual palate of abstract categories (i.e., love, grief, time, death) will soon be subdivided to include: low-level doubt about one’s spouse, mild anxiety caused by notes from one’s boss, fear of the loss of bandwidth, fear of data, suspicion of the apparently authentic, crippling self-doubt masked by expensive shoes. The advertising industry stands to benefit from this new development, as consumer desires are predicted to multiply incrementally.

I disregarded these cards as best I could, tried not to think about them, tried to distract myself with day to day routines. I knew Cloud well enough to know that any attempt to interpret their implications for me personally, American Society in general, or whatever exactly it was that Cloud was implicating, was a fool’s errand.

Despite my disavowals, I continued receiving them with no discernible rhyme or reason. Sometimes two or three might come on consecutive days. Sometimes months would pass without word from Cloud’s network of motor lodges and despite my best efforts, I found myself living in a state of free-floating anxiety, wondering when Cloud’s next missive might darken my mailbox.

On a subzero day in February I received a postal advertisement from The Jackman Station Main Motel, on the back of which Mr. Cloud reported:

In a tiny courtroom in Montana Empathy, God’s own footpath, has been deemed “invasive.” The debate over its legality rages on.

Christ. What was Cloud trying to tell me? Even if I had the inclination, I didn’t have time to consider it because the next day I received a card from the Mountain Breeze Motel in Pigeon Forge Tennessee. The front image depicted a woman hovering mid-bounce above a diving board wearing Victorian Bathing Clothes and a white hair cap on her head, about to plunge into what the card claimed to be the “best in-ground pool in all the South.”

I showed this one to my wife in hopes of finding a stabilizing perspective, some small measure of sanity. After reading it however, she walked out of the house without a word and buried the postcard in the garden next to the arugula. I never asked her why she’d do such a thing, and I continued to refuse to deconstruct Cloud’s message for motive. I refused also to consider that Ahab might have shared some past secret with my wife.

For the record, employing his unparalleled ability to write in infinitesimal letters, Cloud managed to cram the following into the left side of the divided back of that card:

The following words have been trademarked by the Flaming Tiger greeting card company: “Love,” “Grace,” “Loss,” “Sorry,” “Life,” and “Time.” You may still use these words in everyday conversations, but when writing them, you must include quotation marks and the proper citation. Larry Humpwilde, the CEO of the company, made the following statement: “The new trademarks on these old, nearly meaningless words will reinvigorate the common human experience.” The experts suggest that these words will carry a larger emotional impact now that they can be purchased in designer boutiques. The Flaming Tiger company plans to release more affordable versions to denote less intense expressions of emotion. There is, of course, the risk of counterfeit cards, already said to be circulating through the Chinatowns of the nation. Chairman Humpwilde despises these fraudulent vendors, stating, “Counterfeits could have dangerous psychological implications. Imagine finding out that the ‘love’ you felt was not true ‘love’ TM. Imagine that your experience of “life” TM was somehow false.

Every second Thursday for the next three months I received postcards from places where Mr. Cloud was evidently busy losing his mind. From the Madonna Inn in Echo Utah, he informed me that:

Three men from Carlisle, Pennsylvania beat each other to death after they admitted that they loved each other.

Writing from The Cadillac Motel in Fostoria Ohio, Cloud reported that:

A new measurement has been invented to calculate the emptiness felt in the hearts of teenagers who feel that they are somehow responsible for their parents’ divorce. This measurement is part of a global effort to calculate exactly how “sad and fucked up” TM we all are.

And from The Silver Saddle in King City, Cloud warned:

Salad will kill you more slowly than red meat, increasing the possibility for painful illness or depression due to the loss of friends and family and everything that brought one comfort in the old world.

I cracked. I couldn’t not question the messages any longer. I became obsessed, in constant fear and longing for the next one to arrived. Why was Ahab writing these things to me? What was his game? My line of reasoning ran along the following lines: I knew Cloud well enough to know that he was fucking with me, of course; people don’t change that much. I had by this time seen the film he’d made out of Oscar’s Knee and, the merit of that film notwithstanding, it was clear that he was still a devout practitioner of Electric Kool-Aid antics. I tried to satisfy myself with the conclusion that Cloud pictured me reading his insanities in the halls of my domesticity while imagining him rambling footloose in the American Wilds… and he chuckled. Nothing more than that. Getting his kicks. He thought the whole thing was a hoot. He knew that I would find the prank funny too, which admittedly some part of me did, for Cloud and I shared a sort of wry grin view of the world, but he also knew that I’d have to pretend that I was pissed off about the whole theft incident, that I’d be forced to strike a pose of indignation– How dare he toy with me after stealing my project! and so on. He knew my position was such that I’d have to claim insult to injury and I’d therefore be forced to suppress my amusement at the postcard trick he was performing. In other words, I’d be caught in what he liked to call a tension envelope.

The part of my brain I reserve for paranoia, however, had other ideas. It began to suspect secret messages. It wondered if Cloud embedded the missing links to American conspiracy theories in those words. JFK, Jimmy Hoffa, the moon landing, the creamy richness of Velveeta cheese. Did Cloud have the answers? Was I supposed to act on this information in some way? Long nights passed sleepless. I ran the messages through scores of cryptographic code-breaking systems, some of my own invention, agonizing in the basement of my home for endless hours while my family life suffered. I missed Halloween parades and anniversaries only to emerge with empty hands and nearly certifiable. I had to accept that the messages contained no code and shame on me for searching for meaning in a Cloud prank.

I knew in my heart of hearts that Mr. Cloud’s main point is and always has been that there is no point. As I stood on the street in front of my house on a late October day aswirl with beautiful death, I pulled from the mailbox a ghostly image of the Motel Carousel in Dothan Alabama, and I could almost hear him saying, The meaning of meaning is its intrinsic meaninglessness.

I flipped the card in my hand, almost against my will, and read Mr. Cloud’s words aloud to no one at all:

For his continuing effect on the erosion of human vanity and pride the inventor of the whoopee-cushion has been canonized, St. Flatus.

It took me longer than I care to admit to begin analyzing the postmarks. When I did, sometime near the end of the cryptographic period, I realized that something was gravely amiss. First, the zip code origins in the imprints next to the stamp killer bars were wildly inconsistent with the locations of the establishments depicted on the fronts of the cards. For instance, that Alabamian postcard was postmarked in Caldwell Idaho.

This cut across the grain of Cloud’s penchant for the purity of the prank, which, any bedroom critic worth the weightless weight of his own inkless blog knows, called for the cards to be sent from at least the general vicinity of their respective motel’s geographic points of origin.

But as red flags the geographical incongruities paled in comparison to the dates of the postmarks. They were out of order, in both senses of the word now. For instance I received a postcard postmarked March 15th in October while one dated June 12th came in on June 15th along with one dated the previous January.

On each of these he wrote a single sentence. Pieced together the message read as follows:

The tiny town of Eatonville, made famous by its principled stand against technology, has reinstated the use of automobiles. According to one local resident, morale has been falling drastically and SAT scores are dropping since the technological holdout. “It got kind of sad, she said, “seeing lines of limping people trying to beat each other to the podiatrist. Or watching the neighbors carry their dead to the morgue like sacks of potatoes.”

Moreover, the locations from which they were mailed were impossible given the respective dates. A card from the Fort Henry Motel postmarked in Wheeling West Virginia, for instance, was dated just one day after a card from The Acropolis Motel postmarked in Antelope Oregon, locations nearly 2500 miles apart.

This could only be possible if Cloud was operating with an accomplice or traveling by air, which again would undermine the elegance of Cloud’s equation, completely contradicting the “open road in an American car” type mythologies associated with the institution of the roadside motel, and this, if nothing else, was precisely the literary motif Cloud was riffing on. Anyone else, sure. But not Cloud. Cheating by correspondent or traveling by commercial airline to obscure motels in forgotten burgs would go against everything Mr. Cloud stood for, a transgression he was incapable of committing. I knew full well that Mr. Cloud’s nihilism was absolute when it came to the godheads of religion, politics, economic models and so on… but I also knew how devout his faith stood when it came to the rules of tricksterism. Mr. Cloud was a zealot of the minor keys. These things mattered to him.

So now the logistics of the postcards perplexed me as much as the messages written on them. I’d gotten nowhere. Strike that. I was moving backwards.

It got worse. Four days after this revelation an event occurred that threw me into near existential crisis. I received a postcard from the Pelican Spa and Motor Court in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico… postmarked a week after the day I received it. Unless the postal system had been taken over by time travelers, maniacs, incompetents or some combination thereof, something was either terribly wrong or terribly right with the world Cloud was operating in. From his arid perch in the New Mexican desert outside the time space continuum, Mr. Cloud informed me that:

Snow, the physical manifestation of silence, continues to plague the Northeast. Deafmute snowmen stare at each other across suburban lawns through acorn caps, bottle caps, and in one case, a pair of gold teeth with some blood still clinging to the roots.

A week later I received another postcard, this one from a New Jersey motel, a motel, yes, I’d stayed in once with my family as a child. It read:

The majority of each generation is still desperately baffled by mathematics.

It was postmarked the same day I received it. If I were to take that postmark at face value, it meant that Cloud was close, just a three hour drive down the turnpike. Despite the convolution of the postmarks, or perhaps because of it, I took the chance of accepting it as fact and without packing a bag, without saying good bye to my wife and kids, I set off for the Motel Americana to track down my great white whale, Ahab Cloud.

…

You might recall my mentioning that when I first began assembling Oscar’s writings and tapes into podcast form, I’d unearthed a handful of news articles relating to the Motel Americana and the mysterious disappearance of the tenants and proprietors who happened to be staying at the motel on August 15th 1988 and that the building had been mysteriously razed that same night. I had no reason to doubt the veracity of the reports and I never bothered to re-visit the site to see what was left of it firsthand. Now, I kicked myself for this. Receiving Cloud’s postcard from the Motel Americana suggested that he had done his due diligence where I had been lazy. Maybe there was a mistake in the reporting I’d found, or it had been falsified by some internet idiot with nothing better to do than fuck with reality. I couldn’t handle even considering the possibility that had been Cloud all along. That would have meant diabolical scheming I was unprepared to think about.

I moved on and found that the prospect of the motel still standing excited me. The process of working so closely with Oscar’s stories elevated the motel to magical status in my personal mythology. It had become a dimension unto itself, a place wondrous and terrible, a private place in a public space where love and fear slept beside one another in the same queen sized bed. The closer I got to it now, the prospect of actually seeing it in its three dimensional glory became somehow more important than confronting Cloud for his literary theft and postal harassment.

But these hopes were immediately dashed as I pulled off the turnpike and into the crumbling parking lot of the former site of the motel. There was no Motel Americana any more than there’s a Shangri La or Agartha or El Dorado. Left in place of what was once Oscar’s home was nothing more than concrete rubble, bent iron girders, and glass shards no one ever bothered to haul away.

Feeling colossally stupid for having fallen prey to yet another Cloud prank, I sifted through the detritus mindlessly. I managed to unearth some artifacts of lives that may or may not have crossed paths with the motel decades prior, and for reasons I couldn’t explain I loaded these items into my car. A heart shaped locket. An address book. A high heel shoe. A yo yo. A ticket for a Broadway show that ran in the early eighties. And so on.

After the scavenging there was nothing left for me to do, nothing to salvage the time I’d wasted contemplating Cloud’s nonsense or postmarks or lapses in the natural progression of time. Rush hour bore down upon the land and, not exactly thrilled about the prospect of throwing myself back into the fray of New Jersey traffic, I crossed the street to a strip mall where I planned to pass an hour with a beer and a burger at a place called, I shit you not, Pete DeWitt’s End Bar and Grill.

This is where serendipity bestowed upon me the gift of my old friend, Ahab Cloud. I was walking in, he was walking out.

Recognition dawned on his face and with what sounded like a note of merriment lift in his voice he said, Jack, buddy!

I walloped him in the face.

He fell to the asphalt.

Crab-walking backward and attempting to stem the flow of blood gushing from his nose with his sleeve he groveled something about explanation.

You stole The Knee, I growled.

I thought it was half a leg, he said.

Bloody nose and all, he hadn’t missed a beat. It was a line from Oscar’s story, of course, and quintessential Cloud. I couldn’t suppress a grin.

He shuffled to his feet and patted me on the back. Besides, I was just borrowing it, he said. I always meant to give it back, old chap. A knee’s usefulness lasts only so long. They give out after a while you know.

Christ, Cloud. I pulled a bunch of the postcards from my back pocket and shoved them at him. What the fuck?

He shrugged, and said: In the antique postcard game now, ay? Okay, how much you want for them? Let’s start at two bits a card and go from there. I’ll consider only mint condition, of course. I have standards.

I flipped them over, confronting him with his own handwriting. He whistled through the nose blood that was now filling the spaces between his teeth.

We better go inside and start drinking right away, he said, There’s a story you need to hear.

Of course there was.

…

Pete’s feels like a stomach recently evacuated and raw and hungry. Locals start drinking early in the morning and quit early in the evening, not out of any sense of decorum but because the afternoon has taught them once again that a man can only drink so much without deriving a sense of joy from the drunk. Or maybe they just run out of money. Either way, Pete’s drinkers are day drinkers by blood and they know intimately the line where impairment edges oblivion. They tip toe along that high wire back to beds in small rooms just in time for prime time TV to hum them to sleep. This was a week day afternoon, however, so the mood was steady hum. The reassuring account of the Mets’ latest unraveling occupied all three television sets above the bar. The cast out of a Bukowski chased down well whiskey with watery beer and Cloud and I raised a glass to old Hank and joined the ritual without hesitation.

When Cloud began his tale by saying that he believed that he had been sucked into an inter-dimensional wormhole, I immediately realized not only how dumb I’d been for hoping for a reasonable explanation about the postcards, but that I never even really wanted one. What bothered me about the postcards most was that I missed Cloud. Or not being in on the joke. Or maybe who I’d been back when I knew him. Some combination thereof, probably. Listening to him work up a froth of his patented brand of lunacy, I revisited that kid unencumbered by the antithetical feelings of doubt or hauntings of what I may have lost or, worse, gained in the years since those early days. Witnessing the way Cloud’s mind worked, hearing him muse over his carefully constructed insanities, I became that kid again. Full stop. That’s who sat across from Cloud at that time-nicked and cigarette burn scarred table-a young man ready for literary adventure.

At the same time, looking out from those kid’s eyes, I saw for the first time that Cloud appeared tired. I tried not to think about it, or not to see it, but a hint of frailty played in the movements of his mouth as he snuck the second whiskey in between the words. I couldn’t help noticing the eyes set a little deeper. The lines around his mouth a little sharper. He’d grown thinner since I’d last seen him. Paler. I wondered if it was just the normal tyrannies of time’s agency playing out on him or if it was something else, something that had to do with what he was saying had happened to him.

Cloud told me that after wrapping on the last day of film production, he’d checked out of the Motel Americana and drove to his parent’s house to rest and recover. Exhausted in a way that only a no-budget film production can cause exhaustion, he consumed a plate of oatmeal cookies his mom had made for him, washed them down with a giant glass of whole milk, and rolled into the puffy couch in the den just as he’d done so many times when he was in need of safe harbor.

When he woke, however, he found himself on a bed in the shittiest room of the Prairie Winds Motel in a town called Smith Center, Kansas.

Which, Cloud noted, Happens to be the precise geographical center of the contiguous United States.

I bit my lip.

Cloud went on.

Confused and stricken with horror and panic, Cloud crashed out of that motel room into the assaulting expanse of Kansas blue sky. He spun in the dirt parking lot, dizzy, unwell, disoriented. Shielding his eyes from the alien prairie light, he burst into the lobby nearly shattering the pane of glass in the door in the process. The woman behind the desk tried not to acknowledge his appearance and greeted him cheerily. My, you’re up early, Mr. Cloud.

Raving, Cloud pointed at her and demanded to know “the full meaning of all this!”

She informed him that she had no idea what he meant by that question.

After a Beckettian exchange that likely unnerves the woman to this day, she pointed to a name in the register book scrawled in his own hand. The name was Ahab Cloud.

Confused and chastised, questioning his own sanity, Cloud asked with profound meekness if she knew which way New Jersey was. The woman raised an unsteady hand and pointed with trepidation. Cloud followed it.

He set out eastward in his ’99 Isuzu I-Mark, which, having also been somehow transported to the Prairie Winds, stood in the dusty parking lot before Cloud’s motel room door. He consoled himself by claiming fatigue hallucinations the entire twenty plus hour drive back to his parent’s home in Jersey.

Upon re-entering, he refused anymore oatmeal cookies, milk, or even to discuss his day with his perplexed mother and father. He tried the couch again immediately.

Sometime later, he woke up at The Western Star Inn outside of Rifle Colorado.

According to Cloud, this condition still plagues him. Until this morning, he said, It’s never been the same motel twice. Just this week, he said, I’ve woken up in motels in seven different states across the country.

No matter how far he drives, he told me, no matter how long he runs or flies away from the motel he wakes up in on any given day, no matter where he might pass out, he wakes in some other roadside bed with apparently no rhyme or reason.

As he unfolded a map of the continental United States across the table I ran through my pop culture rolodex for references Cloud might be lacing through his narrative. I said, like Ground Hog day.

Except time moves on, he told me. One day here. Pointing to a place in Northern Florida. The next maybe here. His finger hovered over Northern Utah. Or here. The Finger Lakes region.

The map looked to be suffering from a case of chicken pox. No. It was a milky way of red circles with tiny dates next to each one. All the places I woke up, he told me. All the places on your postcards, I’ve been to every one of them. And more. His head lowered. So many more, he said. But not on purpose. I’m trapped. But I’m real, Cloud told me. You have to believe me. I exist.

For the first time, I heard exhaustion in Cloud’s voice. Defeat. It rattled me. I told him to take it easy. It was all going to be all right.

He’d try to stay awake. To outrun it: I drive across states into or away from the sun, four or five at a time, some days caffeine or cocaine addled. I’ve driven this country backward and forward and in circles and squares and triangles more times than I can count. Idaho and Vegas. Gulfs and rivers and mountains. Kansas City and Virginia and barbeque pits on roads leading nowhere. Town gatherings. Holidays. Christmas in Florida and New Orleans. I’ve outrun tornados and sometimes I talk to gatherings of sleepless old men at diners at four in the morning about the state of the country. It all forms a single image in my mind, nebulous, like standing in the middle of a 360 degree movie screen and spinning, the image always changing, always the same. I feel this country the way I feel my childhood, Jack.

He told me that one time he didn’t leave a room for a week straight. He didn’t move, but the room around him and the landscape outside the window changed with every new sun’s dawning. He had no idea what state he was in on any given day.

He makes his living by writing, he told me. That’s the easy part, he said. He fires out articles about pets and shampoo, weather and shoes. Anything you can buy. I review movies and music and food. I don’t need much, he told me. My board is always paid for. I write uplifting motivational blog articles filled with every platitude you can think of. Political opinions for both sides. Ad copy. Anonymous posts for online reputation outfits. It’s a sea of words out there and I’m a Neptune. It’s awful.

But if I had to pinpoint the worst thing about the whole thing, he said, I don’t think it would be that or the brown water coming from the faucets or the paper walls moaning in horrible pantomime of pleasure or even the bed bugs. You know what the worst part might be? It’s that I don’t dream anymore. You understand what that means? Not once since the whole goddamned tilt started awhirl, I haven’t had a single dream.

He looked in my eyes and in a voice I’d never heard asked me, What’s a man who doesn’t dream, Jack? Maybe I’m not alive. Or not really living. That’s what I’m afraid of.

Something like that, he said, That’s what I used to think on those early drives.

Then one day, I don’t know where it was exactly, Mississippi somewhere, I’m standing under a leaky awning outside the lobby of whatever motel and it was raining only the way Mississippi rains. A couple of kids pull into the parking lot. Everything I owned packed into the back of a pick up. Maybe they’re twenty. From Maine or New Hampshire. Full of that thing. You remember it? That thing that deflects bullets off your chest? Laughing at the soaking they got running across the lot.

They stood under the awning with me a minute sluicing water from their skin. Where you guys headed, I asked. The one kid looks at me, the bright gray sky sprawled across his eyes in the half grin, and waved his hand across the rain and the road and everything else under his fingers. Why, to find the American Dream, sir.

How ’bout you, the other kid asked. And I said my line the way I’m supposed to say it, the wizened ex-hipster who hasn’t quite fully surrendered to the death throes of monitoring his 401k. Me? I said, I found the American Dream a few miles back. I can’t tell you what she told me. But I’m done with her. She said she’s looking for you fellahs now.

They got a kick out of that like they were supposed to and went in to the lobby to do their thing, which, if I remember the role correctly, was to harass the desk clerk without her realizing she was being harassed.

It got me thinking that maybe that’s why I wasn’t dreaming, because I was living in a continuous dream.

Cloud’s eyes unfocused. He stared out to something past me, past the bar surrounding us.

And motels, he said, They’re right up there with DiMaggio and Jazz and Astronauts and Nuclear Bombs as far as the American Dream goes. What else could my dream be but the American Dream? That’s what I thought. Where else could an American Dream be dreamt but in a motel room by a guy so lost it doesn’t matter how hard he tries he can’t get to where he wants to be because he can’t get anywhere, not of his own free will. If I never believed in such a thing as free will I wish I did because realizing he don’t have it is a hell of a way to get the stiff punched out of your upper lip.

I walked out into the rain and stood in it thinking she gives you two choices, the American Dream: You either give up and let the world have its way with you and sit down and wait around to die. Or you run and run and run and never get anywhere.

Which is more like a nightmare than a dream, ain’t it?

At some point on a morning soon after that when I forgot to care who I was supposed to be, I looked out my window and caught the rising sun crossing a thousand miles of red rock sand to fill my room with angels. Or maybe it was a pine forest sobbing the dew of ancient gods. A city piled on the stoned hopes of a thousand generations of breaking men. A ravenous sea alight with the infinite glimmerings of the smug and the immune. Whatever it was, all of it maybe, through that motel window I saw everything America is and isn’t in a moment that may have lasted the span of a breath or a decade. I’m no Bill Murray, Jack. I’m Tom Joad.

He pointed again at the map. There and there and there, he said. That’s the American Dream. Horatio Alger was sick, sick man. The riches we make of our rags is just a convenient way of quantifying the distractions we construct to keep us from taking a cold hard look at the dream– the dream where we’re looking around for a better place to call home. Looking forever for it.

Cloud stopped talking. It all sounded crazy to me. He was drunk. And not himself. We both were, or weren’t. Pete’s was empty, truly empty now, and I’d had enough. He read all this in my face and got up from the table. He folded the map drunkenly into his pocket.

Where you going, I asked.

To sleep it off, he said. It’s too late to solve anything now.

When I woke up the next morning I was in my car. I had a dim recollection of following Cloud out of the bar and across the street to the Motel Americana, where it stood proud and beautiful under the neon sign declaring vacancy. I was somehow not surprised by this.

I vaguely remember following Cloud into room 101 as if in a dream. He yammered incoherently for a while, swearing at one point that he hadn’t written those postcards. Hadn’t sent them. Had never seen them before that night. I swear to you, Jack. It wasn’t me. I know it’s my handwriting, just like it’s written in god knows how many register books. I don’t know what to tell you about that. But some nights… some nights when I wake up in wherever USA, I see a kid standing in the shadows of the mirror. Sometimes I hear him mumbling things as he scratches his pencil into a composition notebook. Strange messages I try to grab a hold of but can’t as my dreamless sleep pulls me back down.

I planned to make it to the motel to look around after Cloud passed out but I must have fallen asleep before him. How I woke in my car, I can’t say.

The motel was gone again, of course, reduced to its pile of rubble, and Cloud was nowhere.

Beside me on the passenger seat, however, was a notebook and audio tapes, the ones Cloud had stolen from me that, I found out, contained not just the Knee, but a pile of Oscar’s stories.

One of which, The Double, will be in your feed in the coming days.

1

Subscribe on: Apple Podcasts | TuneIn | Google Play | Spotify | Stitcher | Radio Public | Android | RSS

One thought on “Chapter 10. Cloud Particles”

Comments are closed.