The Motel Americana is a real place. Its name is a fake. All the names you’ll hear, in fact, have been changed, but changed not in order to protect the innocent, and not even to protect the assortment of guilty, ridiculous,desperate, murderous, murdered, maimed, love struck, marginalized and/or woefully tragic lodgers about whom these odd and lovely stories are told, but to protect me, yours truly, Jack Same.

Jack isn’t my real name.

Neither is Same.

And at this point, I’m not even sure if this is my real voice.

Kidding, of course.

But it’s true that I need the cloak of anonymity to protect me from liability because some of what you’ll hear in this podcast is, in fact, fact. Even as inept as my recent investigative inquiries into the matters at hand may have been, I know for sure that at least some of what I’ll relay in this podcast is about people who actually exist, or existed, and some of the stuff that happens in the stories actually happened to these poor people.

I just don’t know how much of it actually happened or how accurately the actions of the aforementioned lodgers have been detailed.

And mixing cocktails of truths and untruths about real people and the things they’ve done, well, that’s pretty much the definition of libel as far as I understand. And also, and this probably goes without saying, I certainly have nothing like written permission to commit their tales to posterity.

But compelled to commit them I am.

First, though, full disclosure: I didn’t even write these stories. I admit, I sit here a mere teller of tales already told, passing along small glimpses into the rooms of a roadside motel as seen and/or imagined by the son of its owner, a kid no older than sixteen.

A kid he may have been, but he happened to be a kid in possession of three gifts: first, a hyper-active imagination, second, a keen eye, and third, enough free time on his hands to teach the first two to dance with one another.

When I think of him now I see him as the kind of kid who sat in the corner behind the motel lobby desk disappearing into the wallpaper while scratching at paper with a pencil. The kind of kid who probably wandered around the hallways of his motel whistling songs of his own making when no one was looking. The kind of kid who’d walk for long lengths of time with his shoes untied, staring at the laces with something like a dare in his eye. Certainly, he watched way too much TV. He probably approached a window in a room he was tasked to prepare and parted the curtains in hopes of seeing something more than the ceaseless stream of motor traffic blocking his horizon, hoping to see, perhaps, a rattled jalopy just then pulling into the lot to deliver a fresh muse to his Motel Americana, a willing customer destined to sign the register book of his odd and lovely stories.

His name, so I gather from the front covers of his composition notebooks, was Oscar Garret.

I never met him. Not directly.

I met his sister instead. Her name was Mandy. And she handed me the worn out cardboard box containing Oscar’s books and cassettes just outside the lobby one humid-sweet summer morning in the mid-eighties.

I was fourteen years old, a couple years younger than Oscar was at the time he wrote most of these stories, and exactly the same age as Mandy when I met her.

It was an unexpected excursion. My father had decided on a whim in the middle of the night to pay a visit to my grandmother who ran a bed and breakfast in Fredericksburg, Maryland. Maybe there was some secret reason for the sudden trip, but if there was, I didn’t know about it. It was presented to us as a light-hearted improvisation, a spur of the moment adventure. My father was like that.

He rolled us out of our beds in our pjs, pillows tucked under our arms, and nudged us into the car. Already divorced at the time, my mother wasn’t there, so I sat in the passenger seat. My two sisters and brother lay on one another in the back seat snoring softly. And though I tried not to, I also fell asleep almost instantly as my father rolled the dial along the glowing numbers of the radio that faded into increasing static the further we drove into the night.

The thump of the Motel Americana driveway roused me and I clearly remember opening my eyes to the blue and red neon letters looming overhead, then watching them disappear behind the building walls as we pulled up closer to the lobby. The second A was out in Americana, a fact which made little difference, phonetically speaking, but thinking back on it now, if it happened to be the third A that had been out, everything may have been different.

My father popped out to check in before I’d fully regained consciousness and was back in the car before my brother and sisters woke at all.

Thought I could do it, he said, but I was starting to doze like the rest of yous. Better safe than sorry.

I nodded, pretending to be more awake than I was. We pulled up to the door.

Considering he used room numbers for the subtitles of all his stories, it safe to say they held some significance to Oscar, and so if I’d known then what I know now, I would have committed ours to memory. But as it stands, I don’t remember what it was. One hundred something probably. It was your standard issue room in what I understood then to be a standard issue motel. An anonymous container built for anonymous strangers.

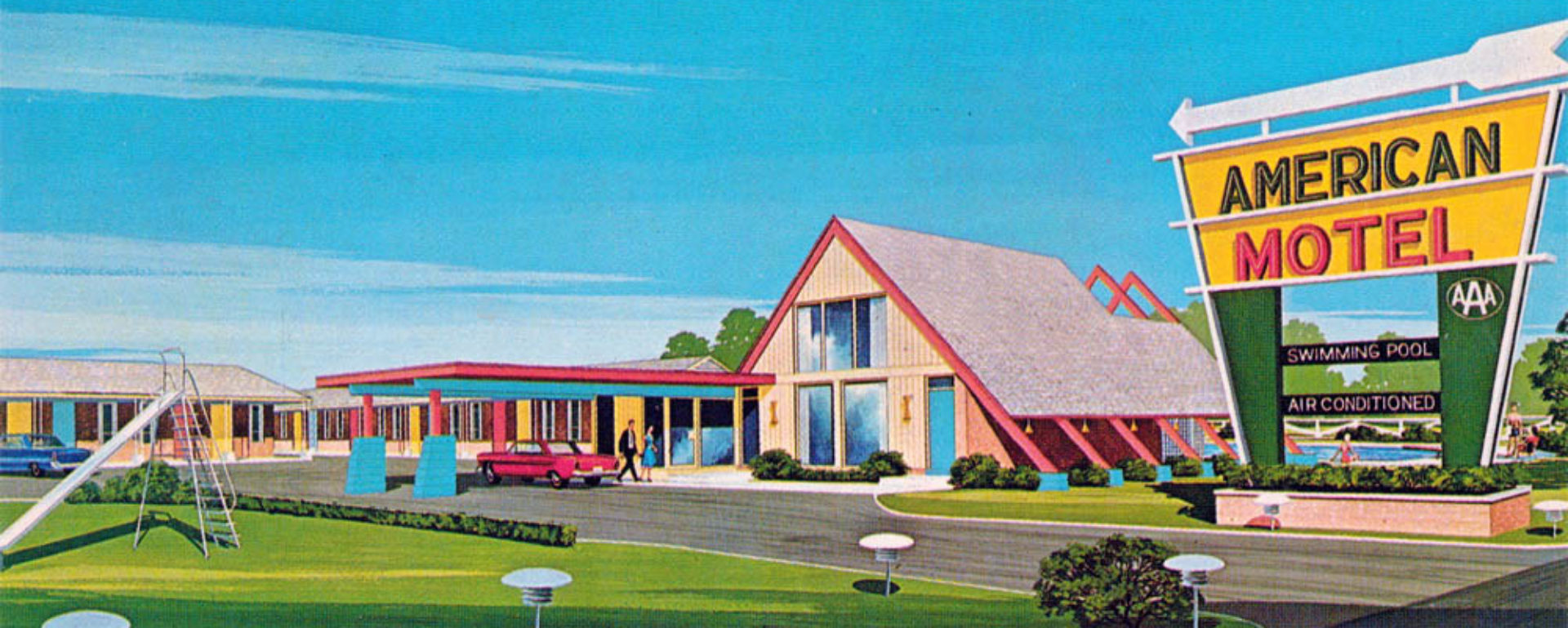

The architecture of the Motel Americana was somewhat unique as far as motels go. It consisted of two types of rooms. There were those in the relatively recent addition Oscar and Mandy’s parents built in the sixties when they bought the establishment. These resembled the structural traits of a modern low-grade chain hotel– two stories of rooms lined on either side of long corridors dotted by strategically placed nooks containing ice makers and vending machines. The others were the types of rooms that differentiate a motel from a hotel. that is, rooms with doors baldly facing outward on their respective parking spots and the highway beyond it.

My father, likely not thrilled about the unplanned expense of the stopover, chose the latter model, the cheaper of the two options.

Inside, two framed art prints hung on the wall– the exact same prints. I was too simple of thought at that age to realize that this fact could very well be interpreted as an ironic artistic statement about the nature of art itself, but I do remember wondering if whoever hung those prints even realized he was hanging duplicates, if he even looked at them at all, or cared,or thought anyone else might. And if not, then what was the point of hanging them in the first place.

This aside, I remember nothing particularly odd about the room. Nothing ghastly, terrifying or surreal. No physically or mentally deranged being knocked on the door. No ghosts or private detectives or unexplained phenomena showed up. Not that I was expecting anything abnormal or life-altering to happen that night, of course, but in retrospect, after knowing what I do now about those rooms, I feel my family and I were either extremely lucky, or extremely unlucky, depending on how you look at it, to make it through the night unscathed by a capital E event.

My younger siblings and I reveled in the novelty of bedding down in a strange place, of course. We surveyed the interior of the empty, faintly sour-smelling mini fridge. We marveled at how the TV channels carried different stations than we were used to at home. We surprised ourselves with Gideon, though we opened the drawer with the explicit intent, and in full anticipation, of finding him there. Reconnaissance over, we promptly fell off to sleep laying head to foot.

I wasn’t the first up in the morning—my oldest sister Joany was already in the bathroom drying her hair—but I was the first out. My father, leaning over the nightstand to fish a Salem out of his soft pack said, You up,Jack? Why don’t you go see if they have any coffee in the lobby up there.

He pulled a couple of bills out of his wallet and handed them to me.

It took the full walk to the office for my eyes to adjust to the August morning light. And just as they did, I stepped back into the pitch black of the lobby. I was blind and she was just a voice. Who are you? What’s your name?

Coffee? I said.

You’re name’s coffee?

I’m looking for coffee, I said. I told her my name.

And where are you from? she demanded.

I don’t remember the room number. It’s over—

No, she barked peremptorily. Where do you live. Are you stupid? When you’re not sleeping in roadside shitholes. I know what room you’re in.

I told her the name of the town two hours north where lived.

Good, she said, You’re honest. And your street address is 36 Hillside Avenue.

It was more declaration than question.

How did you know that?

Your father signed the register book last night. Some people write down fake addresses. I was just double checking. To see if I can trust you.

Oh.

Can you keep a secret, honest Jack Same from 36 Hillside Ave. Edgewater, New Jersey, or do you go around blabbing everything you hear to everyone you know?

My eyes had adjusted to the dark again. She stood behind the brown wood desk striking and, it seemed to me, somewhat shaky. Red hair. Constellations of freckles spun across a nose so small it struck me as impossible. She was wiry thin and looked like she could use her hands to make a fist if she needed to. The room around her was paneled brown wood, I suppose to camouflage the desk, and framed black and white photos hung on the far wall. A rack holding local points of interest flyers collected dust in the corner next to an ashtray urn filled with sand and cigarette butts.

In the silence left in the wake of her question, I heard yelling coming from somewhere outside. I thought she might’ve been crying when I walked in.

I was just sent, I stammered, My father just asked me to get coffee for him. That’s all.

She looked at me for a long minute.

No coffee here, she told me, Just forget it. Then she turned away and stood with her back to me.

Okay, sorry, I said. I began to walk out of the lobby. I stopped briefly at the door and without quite looking back at her I said, I can keep a secret as good as anyone else I guess. Then walked out.

Outside I squinted again through the light toward the sounds of argument. Halfway down the parking lot in the opposite direction of the room where my family was roomed, one of the doors was open. Standing on the walk in front of it was a barrel chested man in a suit with no tie. He had something small in his hand that he was waving in front of another man, a gray haired man who was still in his slippers. Just inside the door, standing in the shadow, was a kid with his head hung. He seemed to be staring at something in the space between his shoes. The small object in the barrel chested man’s hand seemed to be the point of contention, though I couldn’t make out what was being said over the highway’s hum.

The girl came out of the lobby. She had the beat up cardboard box in her hands.

Wait. I’m sorry, she said. Something awful’s happening here today.

I didn’t know what to say to that. The way she avoid looking, I understood it to mean that the awful thing was whatever was happening between the two arguing men and the kid in the doorway.

My brother, she said. They’re going to take these away from him forever and that would kill him. They’re all he has. I was going to try and hide them but I don’t think there’s time.

She shoved the box into my chest and my arms grabbed them by reflex. She darted her eyes over at the altercation ensuing down the row of doors. The boy had stepped out of the shadow of the door and was staring at us.He took another step toward us, but the man in the slippers held him by the arm.

Take these and keep them for him, she said.

For him? I asked.

For us, she said. I’ll come and get them one day, okay?

My eyes touched hers. What’s your name?

Mandy.

What’s in here?

Nothing. Stories. That’s all. But they mean a lot to him. Now go. You keep them safe. Can you promise me that?

I looked at her again.

Promise me that, she said.

Okay.

She released my eyes and looked back down the line of doors at her brother. He tried again to step toward us, but again he was stopped by the man in the slippers. This time more violently.

Mandy pushed me toward my room. Then watched me walk toward the car, where my brother and sisters were already piling in. My father was just coming out of the room with our bags. I stood beside him at the trunk.

No coffee, I said.

Damn. Okay.

I lodged Oscar’s box into a corner.

What’s that? he asked.

Nothing. Old comic books they were giving away. Just sitting in the lobby. For free.

I handed him back the bills he’d given me for coffee as a cop car pulled into the lot behind us. It approached the two men and Oscar in the distance. Mandy was where I left her, but she was turned away, watching the cop car approach her brother, father, and the barrel chested man.

As my father slowed the car to drop the room key in the slot box on the way out of the lot, Oscar finally broke free of the scene that had ensnared him. He was yelling at our car but there’s no way of telling what he was saying. I turned to watch him over the heads of my brother and sisters through the back window as he chased after us. His father was chasing after him. The cop chasing after both of them.

And Mandy was framed in the doorway of the motel lobby watching all of us. Her hand went to her mouth. She was crying.

Oscar flung a rock in a desperate attempt at getting back his stories, then fell to the ground. My father saw much of this in the rear view but didn’t stop. He didn’t even slow down.

You have to be careful about motels like that, he said, The characters hang around those places, you never know. He put distance between us and them. We got back on the highway.

That was the first and last I saw of Oscar and Mandy Garret, rightful heirs to the Motel Americana.

Though I read some of the pages in that notebook during that long weekend at my grandmother’s, I didn’t have the acuity of mind to understand just what it was that had come into my possession, and I was easily distracted– by my grandmother’s pancakes, the railroad track where my siblings and I spent an afternoon flattening pennies.

The audio tapes forged no semblance of realization in my thick skull either. If they produced anything at all, it was confusion. I listened to one of the tapes for maybe five minutes at the most, and what I heard was a lot of sound hiss interspersed by mostly unintelligible voices talking about things with no context to speak of.

I’m embarrassed to say that it wasn’t until I returned to the tapes years later that it dawned on me that the small object in the barrel chested man’s hand was the bug he had found in his room, a bug planted there by a curious kid who liked to listen in on lives he imagined better than his own. At least, more exciting than his own. Stupidly, at the time I didn’t put together that the contents of the box was the evidence that would have incriminated Oscar, and that Mandy had given it to me in order to protect him.

That she loved her brother so much she gave away the thing that most gave his life meaning.

No. What my fourteen year old eyes saw when I looked into that box was Mandy, the possibility of seeing her again. Nothing else mattered really. Any other implication or consequence paled by comparison. I imagined how and when she would show up on my doorstep a million different ways. She would come during a holiday when my whole family was gathered. Or she’d show up when I was alone in the house. Or she would be outside my door on the street waiting for me to come out to go to school. Or she’d knock on my bedroom window while I was sleeping.

But these dreams disappeared like darkness into a night. She never appeared to collect her brother’s stories and the box sat untouched in a corner of the closet, just as it sat unthought of in the corner of my mind. Years passed. Life collected up my days.

My father sold the house and moved down the shore some time when I was in college. All of our childhood stuff, Oscar’s stories along with them, went into a storage unit in South Hackensack, there for us whenever we were ready to reclaim our relics.

He died a few months ago, my father, and in the weeks following his death, while sorting through the details of his life, Oscar’s stories came back into mine.

Before I listened to single tape or read a single page, I punched Motel Americana into my computer. What I found was scant, but significant. A single story, really.

Sometime in the mid-eighties, the year I was there, maybe just days after I was there, some unexplained phenomena occurred. I don’t throw it around lightly, but there’s no other phrase that fits it really. Unexplained phenomena. Everyone who happened to be in the Motel Americana on the night August 22nd, 1988 simply disappeared.

The various missing persons reports all led their respective investigations to the motel and in the final summation, according to the article I found, eight lodgers and the entire Garret Family, had just vanished. No trace was ever found of any of them. No bodies. No traces of struggle or violence. None of them ever showed up again. The investigations are still, as far as I’m aware, still open.

And so after all these years, I finally became obsessed with Oscar’s writings. I read and reread his musings with wonder, and horror, and awe, and joy. I puzzled out the implications of what I’d witnessed in that parking lot so long ago. And I realized, at long last, the literary and phenomenological significance of what I’d been given by that sad red-headed girl that morning.

I planned a trip for me and my family to visit Washington DC as a pretense just so I could stop at the former site of the Motel Americana as we “happened to be passing by.” What I found there was…

Well, I won’t get ahead of myself.

I do plan to hand Oscar’s material over to the authorities. Hopefully, they’ll help bring some sort of closure to the families of the disappeared.

But first, his stories. First, the Motel Americana.