The phone rang the instant Lang touched the door knob. It nearly crushed him, but he entered the room anyway and with an air of feigned nonchalance he forced himself to articulate the thought, It’s probably just the front desk checking to see if the room is okay, though he knew full well that such courtesy calls didn’t happen in motels like this.

He continued the self-delusion: Ah, It’s been a long ride. I’m tired. I need a shower. I don’t feel like talking to anyone. I’ll just let it ring.

So Lang let it ring.

So it rang.

And rang.

And Lang pretended, too, that his fury wasn’t rising exponentially with each of the phone’s outbursts. He tried to ignore it. He tried to will the clattering out of existence. He hummed and listened to his throat from within as a way to neutralize the attack coming from without. It wasn’t a tune he hummed exactly, but a random reverberation playing on his inner ear. It made him think of his mother, the way she’d hum trying to lull him to sleep.

But the tact failed utterly to drown out the irritant so Lang succeeded only in exacerbating the rising fury, which in turn charged the ringing with increased power over him. He boiled. He undressed, suffering, inches away from the frantic twin metal bells inside their plastic body, with the muscles in his jaw so tight he thought he might break a tooth. The throbbing headache he’d been living with since the day the solar storms began suddenly became a sharp piercing, a screeching in terrible chorus with the phone’s siren screams. Lang pressed two fingers to each of his temples feeling as though his skull was under the force of sudden vacuum and about to collapse in on itself.

He took refuge in crashing water. For more than forty-five minutes he steamed himself, biding his time. He ran his aching eyes along the white grouted grid that sectioned off the sea foam green tiles from one another. He pulled the retractable clothesline from its chrome compartment three, four times, wondering idly if the contraption had ever actually been used for its intended purpose, then wondering if a man might manage to hang himself with it. He squeezed shampoo, then conditioner, from their small plastic bottles and ran the gels through his hair in their turn, trying desperately not to hear the hysterical hammer next to the bed.

He convinced himself that the headache was now subsiding, though it surely was not. He tried to concentrate on his two children. He thought of his wife. If she believed the story he’d invented about traveling for work. He never traveled for work. He tried to remember the day he met her. The way she looked at him when she was happy.

Inevitably, Lang depleted the motel’s hot water supply. When it ran over him absolutely frigid, he had no choice but to shut the valves. He stood dripping for a long moment and watched the last of his respite swirl around the drain while the cacophony cried out newly emboldened, ruthless, and unconditional.

He clenched his eyes shut. He tried to see the face of his first child, his son. He tried to remember the boy’s age, his name. The information came to him– Jonathan aged twelve years old— but only after great mental effort. He felt ashamed. Confused. Angry at his confusion and shame.

He’d read about how the electromagnetic effects of the solar storm were causing problems with machines and circuitry across the state, of course. He now wondered if it could also be affecting the mental processes of humans. He wondered if the flares could be somehow aggravating head trauma that had lain dormant since the car accident he was involved in so long ago.

A sob burst unexpectedly from Lang’s throat but he caught himself, stifling his nose and mouth with his right hand before the emotion came gushing. He moved with sudden swiftness from the tub, stumbling over the ledge and landing splayed haphazardly on the bathroom floor. Without taking account of the physical injury he may have sustained, he scrambled to his feet and rushed into the bed room where he lifted the phone, still naked, still dripping, his foot and hip now reporting pain, his mouth now bleeding, to spit out into the receiver, Hello.

The pointlessness of the word stung him at once. The futility. His own ridiculousness. He listened just long enough to hear the voice say:

You plucked blackberries from the tree on your walk home from school

before slamming the receiver back into its cradle.

A precise Mississippi passed while Lang’s head seared.

He saw black.

The phone rang again.

Lang ground his teeth. His right hand made a fist of its own accord. He considered yanking the device out of the wall. He considered fleeing the room and driving somewhere. Anywhere. Driving with the radio off. Silence. No music. No voices. No phones, no goddamn phones. The open road, free of any mode of communication as far as I can see. Take time to clear my head. That would do it. Escape. A bottle of Tylenol and whiskey. Wind and air and angels. Stars. Mile markers and emptiness. No one. A place hidden from the solar flares. Stick my head in a hole in the ground. Wrap it in tinfoil. Anything. Something. Anything.

But he knew none of that would make any difference, either. It would come again, the voice, the ringing. Sooner or later, wherever and whenever he wound up, it’d catch up to him. And he’d ripped more than his share of phones from walls in the past week. At home. From his cubical at work. He’d smashed too many radios. He’d put his foot through both television sets in his family home, scaring the hell out of his wife, causing his children to cry.

He removed the receiver from its hook and laid it gently, almost apologetically, on the nightstand, knowing the voice was there, always there, spurting a continuous stream of words like city water from a broken pipe.

Lang found that he could not recall his wife’s face, her name.

After a terrifying moment, he said aloud into the room, Abby. God damn it, Abby’s her name. My wife. And I love her.

And with the name, the image of her face materialized. He wanted to touch her hair. To kiss the spot on her neck just below the ear that buckled her knees.

He considered returning to the bathroom to dry himself. Instead, fortified by the vision of his wife, he stared at the voice in the phone, indignant, refusing to believe he was so far gone that he needed to flee his home in order to protect those he loved.

He picked up the phone. He put it to his ear. He listened. For the first time he listened to the voice with the express intent of comprehending of what it was trying to tell him. The voice spoke English, at times mangling syntax, at times placing stresses on syllables seemingly arbitrarily:

From a stroller you craned your neck under a canopy of trees.

And with a sudden rush, Lang was there, a child of perhaps three years old, looking up at the sun burst gold then disappear as it passed behind the freckled ceiling of foliage.

The voice said:

You held your father’s hand in the snow.

And Lang felt that, too, the warmth of his father’s giant, rough-skinned hand enveloping his own. Lang wanted to savor the moment- his father had passed while Lang was still in his teens—but the voice obliterated it as it pressed on to the next moment unhaltingly. It plucked arbitrary instants out of Lang’s life like picking cards from a deck spread across a table. It throttled across epochs of Lang’s life with no rhyme or reason or methodology he could ascertain.

You breathed twice then opening your eyes.

A sorrow. A smirk. Chocolate, the first time you tasted.

The sticky touch of honey on Sunday morning. A football. A truckload of bricks in the morning light.

Pastel chalk writing on a sidewalk.

The drawing of a cat you made. The joy in your heart.

Making love in the backseat of car parked in a garage.

Your first pay day, the smell of money in the envelope your boss you handed.

The sound of moonlight.

A black and yellow butterfly flitted, landed then on left shoulder while you ate peanut butter and banana in sandwich during Grove Park.

These were the kind of specificities that initially sent Lang’s mind reeling when he’d first become aware of the voice. He knew from glimpses he’d inadvertently heard over the past couple weeks that many of the occurrences about which it spoke were essentially ubiquitous, but he also knew that occasionally it would describe events and feelings that no one could have known about except for him and, perhaps, his God.

Rearranged priorities. The immortality of being sixteen. When death’s diminished dominion diminished.

You are not what you believe. Your rising pride. Unconfessed feelings. Irritability.

The zip of a zipper in a campground in the Adirondacks you camped.

The smell of rain falling on hot asphalt.

You think. You consider.

Your sister yelling over a blow dryer. You learned to rhyme. To listen. To sing, you sang silent night on a snowy night on the steps of Saint John’s Church.

Your first word absent of meaning, whirled peas clutching.

The joy of reading. Jane and Spot.

The memories the voice triggered rushed to the fore of Lang’s mind faster than he could handle. He felt dizzy. He sat on the bed. He listened.

You flaked flint with your thumbnail. Walked a cold stream barefoot, you did with your toes slightly numb.

You are not what you believe. Resisting new things. Your credit rating.

Chasing snowflakes as they fall. Apple juice in a box squeezing at lunch time.

Morning dew, a sky, aware of being a young man, you believe that all of human endeavor can be defined in artistic terms. You declare on night while drunk that Art is the governing principle of mankind. Religion, politics, common endeavor all fall under the umbrella The Act of Artmaking. Creation. You have never been happier.

Watching television in the morning with snacking of sliced apples. A magic garden then a nap beneath a poster of Spider Man.

The voice went on. Land felt the memories as if they had a physical dimension. As if they had somehow manifested themselves as objects to have and to hold. They produced visceral reactions, a series of reincarnations Lang felt blooming and aching in his chest. A single word would trigger a joy more intense than he’d felt the first time experiencing the occurrence the voice was describing. The next would bear down on him with great sadness or unbearable longing for something long since hermetically sealed and compartmentalized in Lang’s experiential constitution.

A broken bell, knee scrapes on the street, the bicycle chain unhinged.

You gave her diamond earrings and she smiled.

Cigarette smoke and laughter. Wearing rags and grinning wildly, you scoffed and mocked the rich and politicians who were so convinced their riches and power held meaning.

The monitor in the hospital watching with your fingernail biting into the skin on your left wrist.

You are not what you believe. Coffee in the morning is that you must have.

Morning came and went unbeknownst to Lang. He lay on the carpet beside the bed on his back, naked, staring up into the blank screen of the ceiling, watching his life play out across it like a movie. Tears streamed down his face.

Called your first grade teacher Mom and then embarrassed. This is the first time you psychological processes considered.

A BMX bicycle, candy red. The realization that you had no possessions save the things people gave you. Toys. Kisses. Advice and admonitions.

The world is open, anything is possible. You play a mental game where you name the reverberations of the world in all things, matching the infinite echoes of and in all that exists. You see the interconnectedness easily. Wind in footsteps. Birdsong in wine. Color, sound, in emotion and the way trains move across the land. Every surface reflects to some degree. Lines don’t exist. Rise and fall. Repetition. Contrast. Negative and positive space. The world as one. It becomes too much. You take solace in humility.

As many religions as people who walk the earth you believe should be.

Your grandfather sopped red wine with crusty bread. You ate it at his kitchen table in a basement in the Bronx.

You are not what you believe. Miserliness. Your credit rating. Afraid of cancer.

After many hours, Lang at last became aware of the phrase that had been recurring in the voice’s soliloquy. Up till then, seeing no way to fit these lines into the context produced by the proximal remembrances, Lang had simply ignored the anaphora. But this became impossible as morning broke. The phrase increased in frequency. Lang took note.

You are not what you believe. You worry you are not liked. Monthly payments. Well insured.

You are not what you believe. You are an explorer.

You are not what you believe. Your cries for help. This is an effort to make contact.

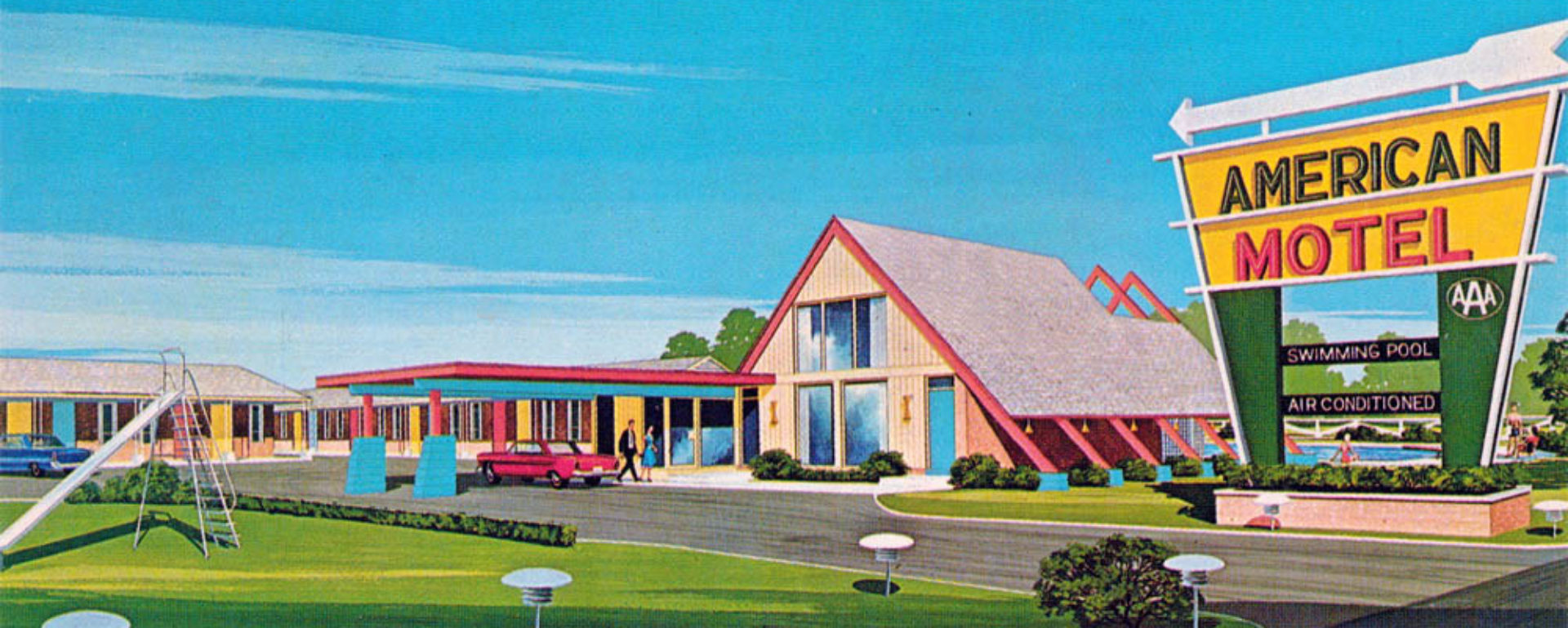

Soon Lang found he was ignoring his life entirely and focusing solely on the phrasings that immediately followed the suspect string of words. A different story of Lang’s life began to emerge. Over the next three hours, he wrote it down on a memo pad branded with the Motel Americana logo.

You are not what you believe. This is an intergalactic transmission carried by electromagnetic waves.

A voice on the solar winds, Lang thought. He omitted the prompt and wrote down only the response phrases.

You are an extra-dimensional traveler on an exploratory mission for your species of origin. You are of a race of essences. We have no bodies. As accurately as we can describe in human language, we are a race of aeriform consciousnesses. An awareness in the ether. On the day you were born into your human body, you traveled on a stream of charged particles released from the coronas of a thousand suns. You moved across a vast chasm and through many shadows of time to manifest in the body incubated in the being you’ve called your mother.

There have been many like you. Some have lived and passed in their times as any human might live and pass. Some have been ostracized. Some cast out of their communities as though they were demons. Some have been embraced and called leaders and prophets. Some have been worshipped as Gods.

You have been a faithful and effective missionary, but evolving technology has allowed the earth race to discover that you are not of them. This happened during your stay in hospital after the car wreck.

Lang hadn’t seen the car coming. Nor should he have. He had the green. The driver in the other car came barreling in from the perpendicular direction, fleeing a crime scene, a convenience store robbery. It smashed into Lang’s car squarely and sent Lang into a spin that ended somehow in the storefront of a Woolworth’s Five and Dime. A mother and child had been killed instantly. If it weren’t for the immediate arrival of the cop car already in pursuit of the crime suspect, and the ambulance’s arrival shortly thereafter, Lang would surely have died that day as well. Someone stopped the blood flow from his severed carotid artery. He was in the emergency room in a matter of minutes.

Subsequent standard procedural blood tests revealed certain imbalances in Lang’s neurotransmitters. Platelet levels of dopamine, noradrenalin, adrenalin, serotonin and acetylcholine were all over the map. More tests were ordered. Then more. Doctors with different faces appeared. At some point they stopped offering explanations to Lang. He was sent to another hospital. And then another without being given the choice.

Lang had no recollection of what the voice told him next:

Government doctors induced coma. Biochemical brain regulators were implanted. The dreamwriters were employed. You stayed under for more than twelve earth years while chemicals producing the effects of experience were released into your brain in slow and steady stream producing simulations of experience. You believed your life was continuing of its own accord. It was not. Your life was scripted by the dreamwriters. Your thoughts and emotions were constantly projected onto screens and carefully monitored. The experts studied your reactions to the dreamwriters’ scenarios while they searched your anatomy for clues to the true nature of your existence.

As Lang listened to the story the voice told him, two mental processes took place concurrently in his brain. First, without actually being aware that it was happening, the entirety of what he had done and seen and felt and touched in the years since the car crash began fading away. He did not mourn the loss because it did not occur to him to do so. His life of the last dozen years simply became transparent and disappeared, much the way a face disappears in a cinematic dissolve to a scene of a landscape vista. If Lang felt anything, it was the sensation akin to that of walking into a room and forgetting what you came to get.

Lang registered the voice on the phone saying:

The residual effects of the dreamwriting will linger for some time but they will soon dissipate leaving scarcely a trace.

Second, Lang remembered waking in a dark lab. His body aching. Sitting up. Sitting the bed for a long time in a room of machines and monitors that were off or otherwise inoperational. Confused and weak, Lang tore the IVs from his veins and the sensors from his skin.

The voice said:

The experiment began to fail. Their biochemical processes began to disagree with your natural state of being. Your brain rejected the narratives the dreamwriters etched into your awareness. We heard your cries for help.

After a length of time, Lang realized that a group of men in lab coats had formed a rough circle around him and were staring intently at him. They were all middle aged or older. They reeked of higher learning and entitlement.

With the voice in his ear, Lang thought, These must have been the dreamwriters. Lang thought briefly about such men. They must be true artists, he thought. Who else but an artist could convince another being of his vision of reality, his order of the universe. Who else but an artist could be afflicted with such a compulsion to do so? Lang knew from the days before he’d become the account manager at the marketing firm of Farberware and Lloyd, from the days when he used to be an artist, of such impulses, that strange mixture of trauma and joy, of confidence and self-doubt, that caused the hunger for public flagellation and universal adoration unique to the artistic psyche.

One of the dreamwriters stepped forward and said, You must be confused. We can help.

Just at that moment, the sun flares must have intensified. All the machines and lights in the room leapt to life and a searing pain ran through Lang’s brain. When he unclenched his eyes, the room was once again dark, the machines off, and the dreamwriters were on the floor convulsing and foaming at the mouth.

The voice told Lang,

Your mission is complete. You have been a good explorer. An effective provider of information.

Lang now remembered fleeing the lab, then finding the exit. Walking along roads. Staggering down the row or doors of the motel until he found one that had been shut improperly. Touching the doorknob. The phone ringing.

Lang’s headache was gone.

The voice said:

We are calling you back.

The voice stopped speaking. Lang listened to the soothing sound of the dial tone for a long minute, just to be sure, and then hung up the phone. It remained silent.

All he had to do now was extract the implants that were trapping his consciousness in the human vessel. He broke one of the drinking glasses carefully. Staring at his body in the mirror, with the largest of the shards, he cut into his gums. Though the blood spilled from his mouth in torrents, Lang did not feel any pain. He successfully removed all four incisors from his mouth. When he cut into the first of the canine teeth, he heard the hissing sound of air escaping.